ハラリ氏による幸福論の後編である。前編には以下からアクセスできる。

仏教のしあわせに関する考え方

There perhaps is another way of understanding happiness. One alternative that receives growing attention from scholars of happiness is the Buddhist view of happiness. Buddhism assigned the question of happiness more importance than perhaps any other religion in history.

しあわせとは何かを理解する方法には、おそらくもうひとつ別の道があります。しあわせの研究者の注目が高まっているのが仏教のしあわせ観です。なぜかといえば、有史上、仏教ほどしあわせの問題を重視してきた宗教はないからです。

仏教の関心は神にはない

The main question of monotheist religions is, given that God exists, what does he want from me. In contrast the main question of Buddhism is, given that suffering exists, how do I get liberated from suffering and enjoy happiness. Therefore for the last 2,500 years Buddhists have systematically studied the essence and causes of happiness which is why there is a growing interest among the scientific community in Buddhism.

一神教徒は神の存在を前提とします。彼らの主要関心は神は彼らに何を望むかにあります。これに対して仏教徒は苦悩の存在を前提に、いかにして苦悩から解放され、しあわせを享受するかに関心を集中します。過去2,500年もの間、仏教徒はしあわせの本質と原因を体系的に研究してきました。この点が科学者の間で仏教への関心が高まっている理由なのです。

For example, today brain scientists are taking Buddhist monks and asks them to sit in the laboratory and meditate; and they connect them to all kinds of electrodes and brain scanners, and scan their brains to see what happens when these monks meditate. A lot of researchers of this kind are going along today. Buddhists share the basic insight of the biological approach to happiness, namely that happiness results from processes or carrying within one’s body, and not from events happening in the outside world. So this is something very similar in Buddhism and biological approach to happiness.

たとえば、脳科学者は僧侶に実験室に来て瞑想してもらい、いろいろな電極などを僧侶に付けて脳波スキャナーで彼らの瞑想中の脳波を測定します。このような実験を行う研究者はたくさんいるのですが、しあわせに関する生物学的な洞察に関して仏教徒も基本的には科学者と同じ意見です。しあわせは体内プロセスの結果であって、外界で発生するイベントではないというのです。つまり仏教も生物学もしあわせへのアプローチは似ているわけです。

仏教は快の感情を追いかけない

However, starting from the same insight, Buddhism reaches a very different conclusion. According to Buddhism, most people identify happiness with the pleasant sensations and feelings in the body, while identifying suffering with unpleasant feelings. People consequently ascribe immense importance to what they feel; people crave to experience more and more pleasures while avoiding as much as possible pain and unpleasant feelings. Whatever people do, whatever we do throughout our lives; whether we scratch our leg or move slightly in the chair, or we fight world wars―whatever we do, we are just trying to get pleasant feelings.

ところが、同じ洞察から仏教はまったく異なった結論を導き出します。仏教によれば、多くの人は体内でこみあげる快楽や感情がしあわせで、不快な感情が苦悩だと認識します。その結果、自分の感情を非常に重視します。そしてより大きな快楽を求め、なるべく苦痛や不愉快を避けようとします。人の行いは、それが足を掻くことであろうと、坐り位置をちょっと直すことであろうと、世界大戦を戦うことであろうと、原則、喜びの感情を得るためのものです。

The problem, according to Buddhism, is that our feelings are no more than fleeting vibrations, changing every moment like the waves in the ocean. If, five minutes ago, I felt very joyful and purposeful; now these feelings from five minutes ago are gone; and I might feel sad and dejected. So if I want to experience pleasant feelings, I have to constantly chase them while constantly driving away the unpleasant feelings. Even if I succeed, I immediately have to start all over again without ever getting any lasting reward for all my troubles. Because these pleasant feelings I felt five minutes ago are gone, I have again and again and again to chase them, to get them.

仏教によれば、問題は人間の感情は、海の波のように時々刻々移り行くこころの振れに過ぎないことにあります。5分前、目的意識に満たされ大きな喜びを感じていたわたしは、それらの感情が過ぎ去れば悲しく落胆するかもしれません。喜びの感情を感じていたいなら、不快な感情を避けながら、つねに快の感情を追っかけなければなりません。たとえ喜びの感情を得たとしても、ずっと続く苦痛へのご褒美は得られないため、また一から喜び探しを始める必要があります。5分前にわたしが感じていた喜びはすでになく、わたしは何度も何度も喜びを追いかけ、つかまえようとします。

仏教のこころ観

What then, asks Buddhism, what is so important about obtaining such ephemeral prizes? Why struggle so hard throughout our lives to achieve something that disappears, almost as soon as it arises? These fleeting vibrations of feelings?

仏教は尋ねます。そんな刹那のご褒美を得ることの、どこがそんなに重要なのか?なぜ生涯、生じては消え去る、こころの揺れをそんなに一所懸命追い求めるのか?と。

According to Buddhism the root of suffering is not the feeling of pain, and not the feeling of sadness, and not even the feeling of meaninglessness. Rather, according to Buddhism, the real root of suffering is this never-ending and pointless pursuit of ephemeral feelings, which causes us to be in a constant state of tension, of restlessness, and of dissatisfaction.

仏教は教えます。苦悩の源は苦痛や悲しみの感情にはないし、人生に意味を感じられないことにさえない。苦悩の本当の源は、刹那的感情を飽くことなく、とくに意味もなく追い求めることにある。その追求が人間をずっと緊張し、落ち着かず、不満足な状態に追い込んでいる。

Because of this pursuit of pleasant feelings, our mind is never satisfied with reality as it is. Even when we experience something pleasant, some pleasant feeling, we are not content because our mind fears that this feeling might soon disappear; and we crave that this feeling should stay and intensified.

快の感情を追い求めれば、人間のこころは現にあるものに絶対満足しない。楽しい感情を味わえば味わうで人間は、その感情がすぐに消え去るのを恐れて満足しない。この感情をずっと感じ続けたい、もっと強く感じたいと願うようになる。

苦悩からの解放は快の追求に非ず

People are liberated from suffering not when they experience this or that fleeting pleasure which immediately disappears; but rather people are liberated from suffering when they understand the impermanent nature of all their feelings, and therefore stop craving them and chasing them; and this is the aim of Buddhist meditation practices.

すぐに消え去る快の感情を味わうことが苦悩からの解放なのではない。あらゆる感情は永続しないことを自覚し、それらを求めたり追いかけたりするのを止めたとき、苦悩から解放されるのだ。仏教が瞑想を実践する目的はそこにある、というのです。

瞑想の意味

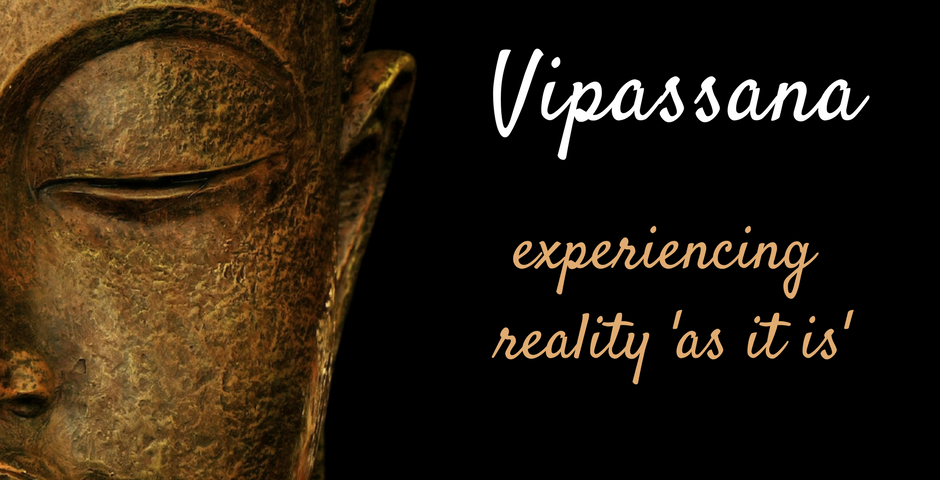

In meditation, you’re supposed to closely observe your own mind and body, to witness for yourselves the ceaseless arising and passing of all your feelings; and thereby to realize how pointless it is to chase after them, to pursue them.

And, when the pursuit stops, the mind becomes very relaxed, very clear, very satisfied. All kinds of feelings still go on; they are rising and passing; they still join anger, boredom, and lust that arise and pass. But once you stop craving to have particular feelings, then you can accept whatever comes―you can accept whatever feelings that come, just watching more, just watching it coming and going without losing your head over them.

瞑想で求められるのは自分のこころとからだをじっくり観照し、あらゆる感情が絶え間なく生起する有様を自分自身で目撃すること、そして、うたかたのごとき感情を追いかけ、追い求めることの無意味さを自覚することです。

無意味な追及をやめたとき、こころはとても落ち着き、とても明瞭になり、とても満足します。あらゆる感情は相変わらず浮かんでは消えています。感情とともに怒りや退屈や渇望が生じては過ぎ去ります。でも、特定の感情を追い求めるのをやめると、何が来ても受け入れられるようになります。湧いてくる感情を受け入れ、ただ眺めていると、我を失うことなくその消長を観察できるようになります。

静穏の境地

The resulting serenity, according to the Buddhist view, the resulting serenity is so profound that people who go on living their lives in a frenzied pursuit of pleasant feelings can hardly even begin to imagine what it is like to be out, to be outside of this pursuit.

その後にくる静穏、仏教によれば、この静穏なこころはとても奥深いものです。それは快の感情を追い求める人生を続けている人には、快の追求の外はどうなっているのか想像さえできないような境地だといいます。

西洋の仏教受容とその誤解

Now this idea is so alien to the modern Western culture that, when the Western New Age movements encountered Buddhist philosophy and Buddhist meditation and all these Buddhist insights, they turned them upside down; turned them on their head.

The New Age cults frequently argue that happiness does not depend on external conditions in the outside world-happiness depends only on what we feel inside. So people should stop pursuing external achievements such as wealth, beauty, and status; and instead connect with their inner feelings. All, as many New Age cults put it, in brief, all happiness begins within. Now this is exactly what biologists argue, but it is more or less opposite of what Buddha said.

このような仏教思想は現代の西洋文化にはまったく異質です。そのため、西洋のニューエイジ運動が仏教の哲学や瞑想などの省察に出会ったとき、彼らは仏教思想を逆さまに理解しました。頭でわかろうとしたのです。

ニューエイジ諸派のありがちな議論は、しあわせは外部世界の外的条件には依存しないというものです。しあわせは内面の充実にあります。ですから、富や美しさや地位などの外面的達成を追い求めるのはやめて、自分の内面の感情とつながりましょう、というわけです。煎じ詰めれば、「しあわせは内側に始まる」とニューエイジ運動は主張するわけです。これは生物学者と同じ見解ですが、多かれ少なかれ、ブッダのいったこととは反対です。

解放はからだの外側にも内側にもない

Buddha agreed with modern biology and with modern New Age movements in that happiness is independent of external conditions. Yet his more important, and far more profound, insight was that the true happiness is also independent of our inner feelings.

しあわせが外的条件に依存しないという点ではブッダも現代の生物学者やニューエイジの運動家に賛成するでしょう。しかし、もっと大事な点は、もっと意味深いブッダの洞察は、本当のしあわせは人間の内側にも存在しないという点にあるのです。

Indeed, the more significance we give our inner feelings, the more we crave for them, the more we suffer. The basic recommendation of Buddhism is not merely to slow down the pursuit of external achievements; but, above all, to slow down the pursuit of inner feelings.

内面の感情を重視すればするだけ、人間は内面にこだわり内側を掘り進みます。仏教が基本的に勧めているのは、外的な成功の追求から遠ざかるのと同時に、内面の感情の追求からも遠ざかることです。

しあわせの歴史は思い違いの歴史?

If we accept this view of happiness, then our entire understanding of the history of happiness might have been misguided: Maybe it isn’t so important whether people enjoy pleasant feelings, and whether people feel that their life has meaning. The main question is whether people understand the truth about the nature of the feelings. And what evidence do we have that people today in the 21st century understand this truth any better than ancient foragers or medieval peasants? So this is the Buddhist view.

このブッダの洞察を受け入れるなら、人類の幸福追求の歴史は全体としてとんだ見当違いだったのかもしれません。内側に喜びの感情を感じること、あるいは人生に意味を見つけることはそれほど重要なことではないのかもしれません。なぜなら大事なのは、自分の感情の真実、その本当の性質を理解することだからです。実際、21世紀に暮らす人間が、太古の採集民や中世の農民より、この感情の真実をよくわかっているという証拠はあるでしょうか?以上が仏教のしあわせに関する考え方でした。

しあわせ観の優劣判定は時期尚早

Now this is not the time and place to judge, to try to judge between all these different approaches to happiness. Scholars began the scientific study of happiness only a few years ago; and we are still just formulating initial theories and searching for the appropriate research methods. It’s much too early to jump to conclusions and to end the debate before it hardly even began. What is important at this stage is to get to know as many different approaches to happiness as possible, and to remember to ask the right questions.

ここまでしあわせに関する考え方を3つ紹介してきましたが、ここはどれが優れているか劣っているかを判定する場ではありません。学者がしあわせの科学的研究を初めてまだ数年しか経っていません。まだ最初の理論をつくり、適切な研究方法を模索している段階にあります。始まりたての段階でいきなり結論に飛びつき、議論を終わらせる必要はないでしょう。現時点で大切なのは、正しい問いを問うことを忘れないように、しあわせに対するアプローチをなるべくたくさん学ぶことです。

人間の内面に関する歴史知識の欠落

Most history focus on the ideas of great thinkers on the bravery of warriors, on the charity of saints, on the creativity of artists. Most history books, however, have much to tell us about social structures, about the rise and fall of empires, about the invention and spread of technology. But most history books have much less to tell us about how all this has influenced the suffering and the happiness of individuals.

人類史の議論においては、戦士の勇敢さ、聖職者の慈愛、芸術家の創造性などに関する偉大な思想家の意見に焦点を合わせるきらいがあります。しかし多くの歴史書には、社会の仕組みや、帝国の興亡や、技術の発明や普及に関する情報がたくさん記録されています。ところが、歴史書には、そうした諸々が個々の人間の苦悩やしあわせにどう影響したかについてはあまり記録していません。

未来を含めてこそ歴史

And this is the biggest lacunae, the biggest hole in our understanding of history. We don’t really know how all this impacted happiness in the world. So we had better start filling this hole because, without knowing this, we can’t say that we actually understand history; and, with this thought, we end our journey through the human past from the Cognitive Revolution 70,000 years ago to the present. During these 70,000 years, a lot of things happened: we are just not sure whether it was all good or bad.

But there is still one more subject which we need to address before terminating this course about a brief history of humankind and this subject is the future. We’ve talked a lot about the past but history also includes the future.

歴史を理解するとき、これは大きな欠損といわねばなりません。その欠損のせいで環境変化が人のしあわせに与えた影響がわからないのです。この穴を埋める努力を始めるべきでしょう。そうでないと本当に歴史を理解したとはいえないからです。逆にこの穴を埋める努力がなされれば、7万年前の認知革命以来の人類の来歴に関する旅を終えることができます。この7万年の間、多くのことが起きました。それが良かったのか悪かったのか誰も確かなことはいえません。

このコースを終える前に、まだ扱っていないテーマがもう一つ残っています。それが未来です。これまで過去について多くのことを話してきましたが、未来も含めてこそ歴史といえるのです。

<講義終わり>

当サイトのハラリ氏関連記事

ハラリ氏の本

主に人類の過去を扱った出世作

|

サピエンス全史(上) 文明の構造と人類の幸福 [ ユヴァル・ノア・ハラリ ] 価格:2,052円 |

|

サピエンス全史(下) 文明の構造と人類の幸福 [ ユヴァル・ノア・ハラリ ] 価格:2,052円 |

解説本

|

価格:1,080円 |

こちらでは人類の未来を扱う(続編的な位置づけ)

|

ホモ・デウス 上 テクノロジーとサピエンスの未来 [ ユヴァル・ノア・ハラリ ] 価格:2,052円 |

|

ホモ・デウス 下 テクノロジーとサピエンスの未来 [ ユヴァル・ノア・ハラリ ] 価格:2,052円 |

![]()

コメント