【ドラッカーの思想】”時代遅れ” とされたキルケゴールの遅れようがない実存哲学(前編)

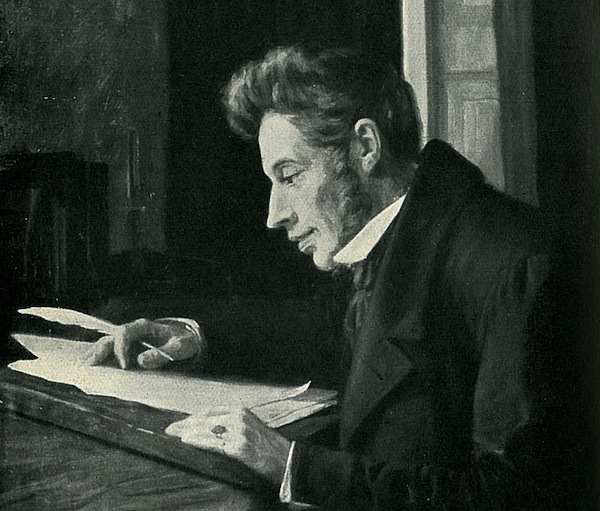

ドラッカーといえばマネジメント。企業経営を学問に高めた人である。ドラッカーの著作はすべて企業や未来社会など組織に関するものだが、一度だけ、組織について書かなかったことがある。キルケゴールに関する論文(「もう一人のキルケゴール」、原題 “The Unfashionable Kierkegaard”、1949年)だ。今回から二回に分けて紹介しよう。

実存主義と社会思想

「もう一人のキルケゴール」は西洋思想史の簡潔な要約になっているから勉強になる。同時に、現代人がいかに19世紀の地続きの時代を生きているかを痛感させてくれる。

リベラル全盛の昨今、相変わらず人はキルケゴールやドラッカーの問いをよけて歩いている。19世紀的進歩主義の限界を、本質的には反省も克服もしていないのである。

なお、本サイトで紹介するのは論文の一部である。全文は以下の本に収録されている。

◆アマゾン

イノベーターの条件―社会の絆をいかに創造するか (はじめて読むドラッカー (社会編))

◆楽天市場

イノベーターの条件 社会の絆をいかに創造するか/P.F.ドラッカー/上田惇生【3000円以上送料無料】

合理主義的進歩思想への違和感

Like all religious thinkers, Kierkegaard places in the centre the question: How is human existence possible? All through the Nineteenth Century this question – which before had been the core of Western thought – was not only highly unfashionable; it seemed senseless and irrelevant. The era was dominated by a radically different question: How is society possible?

Rousseau asked it, Hegel asked it, the classical economists asked it. Marx answered it one way, liberal Protestantism another way. But in whatever form it is asked, it must always lead to an answer which denies that human existence is possible except in society.

あらゆる宗教思想家同様、キルケゴールの中心的問いは「人間の実存はいかにして可能か?」に置かれている。西洋思想史の核であったこの問いは、19世紀を通じて時代遅れになったばかりでなく、無意味で他とは関係のない問いとなった。時代を支配したのはそれとは根本的に異質な「社会はいかにして可能か?」という問いであった。

この問いはルソーが問い、ヘーゲルが問い、古典派経済学者たちが問うた。マルクスはそれにひとつの解答を与え、プロテスタントたちが別の解答を与えた。いかなるかたちで問われようと、この問いへの答えは社会なくして人間の実存は不可能とする点で共通していた。

Rousseau formulated this answer for the whole era of progress: whatever human existence there is; whatever freedom, rights, and duties the individual has; whatever meaning there is in individual life – all is determined by society according to society’s objective need of survival.

The individual, in other words, is not autonomous. He is determined by society. He is free only in matters that do not matter. He has rights only because society concedes them. He has a will only if he wills what society needs. His life has meaning only in so far as it relates to the social meaning, and as it fulfils itself in fulfilling the objective goal of society. There is, in short, no human existence; there is only social existence. There is no individual; there is only the citizen.

ルソーは彼の答えを人類の進化史全体に適用した。人間はどのように実存するのか、個人がどんな自由や権利や義務を持つのか、個人の人生にどんな意味があるのか―、そういうことはすべて、社会が存続するための客観的なニーズに基づいて社会の側が決定する。

言い換えれば、個人は自律性を持たず、社会によって律される。個人は社会にとって重大でない事柄においてのみ自由であり、社会が認める範囲においてのみ権利を持つ。個人が望んで構わないのは社会が必要とする物事のみである。個人の人生は、それが社会的意味に関係するとき、社会の客観的な目標を満たすときのみ意味を持つ。簡単にいえば、人間に実存などというものはない。あるのは社会存在としての人間だけである。個人は存在せず市民だけが存在する。

二律背反を生きる緊張

このような個人と社会を逆立ちさせた思想が隆盛を極めた結果がナチズムと共産革命であり、それらは人類に高すぎる代償を支払わせた、とドラッカーはいう。ルソー的な社会契約思想の危うさを直観し批判していたのはキルケゴールだけではなく、ニーチェやバルザックも同様の危機を感じ取っていた。

しかし、ドラッカーによれば、「人間の実存はいかにして可能か?」に答えを与えたのはキルケゴールだけである。

Kierkegaard’s answer is simple: human existence is possible only in tension – in tension between man’s simultaneous life as an individual in the spirit and as a citizen in society. (中略)

キルケゴールの答えはシンプルだ。人間の実存は緊張のなかでのみ可能だという。霊的な個人であると同時に社会の市民である―、そのような二重性を同時に生きる緊張関係のなかにのみ人間は実存する。(中略)

時間相と永遠相

Existence in time is existence as a citizen in this world. In time, we eat and drink and sleep, fight for conquest or for our lives, raise children and societies, succeed or fail. But in time we also time. And in time there is nothing left of us after our death. In time we do not, therefore, exist as individuals. We are only members of a species, links in a chain of generations. The species has an autonomous life in time, specific characteristics, an autonomous goal; but the member has no life, no characteristics, no aim outside the species. The chain has a beginning and an end, but each link serves only to tie the links of the past to the links of the future; outside the chain it is scrap iron. (中略)

時間の相において人間は世界内の市民として存在する。時間のなかで、人は飲み食い眠る。何かを勝ち取るために、あるいは生き残るために戦う。子どもを育て社会を養う。成功し失敗する。しかし時間のなかでは人そのものが時間的存在であり、死ねば何も残らない。時間のなかで人は個人として存在しない。人は種の一員、世代をつなぐ鎖の一部に過ぎない。時間のなかで種は自律的な生命を持つ。具体的な特性を持ち、自律的な目標を持つ。だが、種の成員には種の外部に生も特性も目的もない。鎖には始めと終わりがあるが、ひとつひとつの環は過去と未来をつなぐ役目しか持たない。鎖を外れた環は鉄くずに過ぎない。(中略)

In eternity, however, in the realm of the spirit, “in the sight of God,” to use one of Kierkegaard’s favourite terms, it is society which does not exist. In eternity only the individual does exist. In eternity each individual is unique; he alone, all alone, without neighbours and friends, without wife and children, faces the spirit in himself.

In time, in the sphere of society, no man begins at the beginning and ends at the end; each of us receives from those before us the inheritance of the ages, carries it for a tiny instant, to hand it on to those after him. But in the spirit, each man is beginning and end. Nothing his fathers have experienced can be of any help to him. In awful loneliness, in complete, unique singleness, he faces himself as if there were nothing in the entire universe but him and the spirit in himself. Human existence is thus existence on two levels – existence in tension.

しかし、永遠の相においては違う。霊の領域においては、キルケゴールの好んだ云い方を用いれば「神の眼から見れば」、存在しないのは社会であり、存在するのは個人だけである。永遠において個人は誰もが独自に存在する。個人はひとり、まったくのひとりであり、そこには隣人も友人も、妻や子どもたちもいない。個人は己の霊に向き合うのみである。

社会という時間相においては、始めを始める人間はおらず、終わりを終わる人間はいない。各人は営々たる過去を受け取り、ほんの一瞬それを運び、後裔に受け渡す。しかし永遠相においては、各人が始まりであり終わりだ。先人たちの経験は何の助けにもならない。恐るべき孤独、各人に固有な全き単独性のなかで、人は宇宙全体に己しか存在しないかのように自分自身と、己の霊と向き合う。このように人間とはふたつの相の間に、両者の緊張のなかに実存するのである。

人間は霊的存在か?社会的存在か?

時間はいくら積み重ねても永遠にならない。両者は相(質)が異なるので交わりえない。そのように考えるキルケゴールは完全に同時代の非主流派だった。

St. Augustine had said that time is within eternity, created by eternity, suspended in it. But Kierkegaard knew that the two are on different planes, antithetic and incompatible with each other. And he knew it not only by logic and by introspection, but by looking at the realities of nineteenth-century life.

聖アウグスティヌスは時間は永遠のうちにあると言った。時間は永遠によって創造され、永遠のなかに宙づりにされていると。しかしキルケゴールは両者は相が異なり、取り換えがきかず両立しえないことを知っていた。彼はこれを理屈のみで知ったのではない。内省により、19世紀の生活の現実をじっと観察することにより知ったのである。

社会と霊に引き裂かれる実存

It is this answer that constitutes the essential paradox of religious experience. To say that human existence is possible only in the tension between existence in eternity and existence in time is to say that human existence is only possible if it is impossible: what existence requires on the one level is forbidden by existence on the other.

For example, existence in society requires that the society’s objective need for survival determine the functions and the actions of the citizen. But existence in the spirit is possible only if there is no law and no rule except that of the person, alone with himself and with his God.

Because man must exist in society, there can be no freedom except in matters that do not matter; but because man must exist in the spirit, there can be no social rule, no social constraint in matters that do matter. In society, man exist only as a social being – as husband, father, child, neighbor, fellow citizen. In the spirit, man can exist only personally – alone, isolated, completely walled in by his own consciousness.

キルケゴールの答えは宗教的経験の本源的逆説を構成する。人間の実存が永遠相の存在と時間相の存在の緊張においてのみ可能だということは、人間の実存は不可能であるがゆえに可能だという矛盾に行き着く。一方の相で要求される存在は他方の相で禁じられているからである。

たとえば、社会的存在としての人間は、社会を存続させるための客観的なニーズが、市民の役割と行動を決定することを要求する。しかし霊的存在としての人間は、己自身と神を律する霊の法と掟においてのみ存在しうる。

人間は社会内に存在しなければならない。そうである以上、社会における自由とは各人にとって本質的に重要でない事柄に関してのみの自由に過ぎない。しかし同時に人間は霊的世界に存しなければならない。そうである以上、各人に本質的に重要な事柄に関しては、社会的掟や社会的制約など本来ありえない。社会において人は夫、父、子ども、隣人、仲間など市民としてのみ存在する。霊の領域において人はその人自身として、自意識の壁に完全に囲まれた単独の孤立した存在としてのみ存在するからである。

Existence in society requires that man accept as real the sphere of social values and beliefs, rewards and punishments. But existence in the spirit, “in the sight of God,” requires that man regard all social values and beliefs as pure deception, as vanity, as untrue, invalid, and unreal. Kierkegaard quotes from Luke 14:26, “If any man come to me, and hate not his father and mother, and wife and children, and brethren and sisters, yea and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple.” The Gospel of Love does not say: love these less than you love me; it says hate.

To say that human existence is possible only as simultaneous existence in time and in eternity is thus to say that it is possible only as one crushed between two irreconcilable ethical absolutes. And that means (if it be more than the mockery of cruel gods): human existence is possible only as existence in tragedy. It is existence in fear and trembling; in dread and anxiety; and, above all, in despair.

社会的存在としての人間は、社会の価値や信念、社会の与える報酬や罰―こうした領域を本物として受け入れることを要求される。これに対して霊的存在としての(「神の眼から見た」)人間は、あらゆる社会的価値や信念を、虚偽、虚栄、不実、無効、まやかしと見なすよう要求される。キルケゴールはルカ書14章26節を引用する。「もし、だれかがわたしのもとに来るとしても、父、母、妻、子供、兄弟、姉妹を、更に自分の命であろうとも、これを憎まないなら、わたしの弟子ではありえない」。愛の福音は「あなたがわたしを愛するより少なく愛せ」とは言わず、単に「憎め」と言う。

人間の実存が時間と永遠のなかに同時に存在するときのみ可能だということは、両立しえない絶対的倫理の間で引き裂かれることを意味する。人間の実存が残酷な神への嘲り以上のものであるならば、それは悲劇においてのみ可能である。人間は恐れおののきながら、畏怖と不安のなかに、とりわけ絶望のなかに実存する。

This seems a very gloomy and pessimistic view of human existence, and one hardly worth having. To the Nineteenth Century it appeared as a pathological aberration. But let us see where the optimism of the Nineteenth Century leads to. For it is the analysis of this optimism and the prediction of its ultimate outcome that gave Kierkegaard’s work its vision.

人間がほとんど生きるに値しないかのような悲観的で暗澹たる実存観だ。19世紀はこれを病理的な逸脱と見なした。しかし19世紀の楽観主義がどこに帰結したかを見えば、キルケゴールの思索にそのようなビジョンをもたらしたのは、まさに19世紀的楽観主義の分析とその必然的帰結の予見だったのである。

<記事引用終わり>

実存から欲望の解放へ

本記事のはじめに「19世紀的進歩主義の限界を、本質的には反省も克服もしていない」と書いた。それはたとえば、こういうことだ。

ナチズムや共産主義の全体主義社会に懲りた人類は、社会的存在として実存することを極小化し、個人主義を最大化する方向へ向かった。この場合の個人は、キルケゴールやドラッカーの志向した霊的実存としての個人ではない。むしろ霊性を捨象した、欲望の主体としての個人だ。実存ということばが虚しく響くような、すっかすかの個人である。

かつては社会に奉仕する生き方が規範だった反動が、社会からの遊離を促し、経済的自由など欲望の追求が奨励されている。それは消費を生命線とする資本主義にも好都合である。

最近流行りの社会正義や新自由主義も結局は、霊的実存から目を背け、個人の欲望の追求にすべてを収斂させる方便のように見える。

次回は続編をお送りする。

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません