【金融の歴史02】高利貸しのタブーが解かれた理由(続)・カネにまつわる名言集

前回に続き、高利貸しに対する考え方の変化を追っていこう。

金貸しはいかにして罪であることをやめ、社会的信用のある仕事になったのか?

テンプル騎士団と金融の普及

Even while clergy such as Cardinal de Vitry preached fire and brimstone against usury, the Church was increasingly willing to borrow money itself. Debt became essential to fighting wars, which both monarchs and the Pope needed to fund.

Europe’s first real private bank had been founded in the 1100s by the Knights Templar, a Catholic military order that fought in the Crusades. The Knights protected pilgrims who travelled to the Holy Land, and this protection included safeguarding their funds by allowing pilgrims to deposit money in Europe and withdraw it in the Holy Land.

Over time, the Templars offered a greater range of financial services; one of their loans relied on Crown Jewels as collateral. The Knights Templar disbanded in 1312, but other bankers extended the practice of lending until, by the 1500s, merchants were buying and selling business debts in fairs across Europe.

ド・ヴィトリのような聖職者が地獄の責め苦を力説している傍らで、教会自身がどんどんカネを借りるようになっていった。戦争を戦うには君主も教皇も資金が要り、いくらでもカネが必要だったからだ。

1100年代のこと、十字軍で戦ったテンプル騎士団によってヨーロッパ初となる本格的プライベートバンクが設立された。騎士団はエルサレムの聖地に旅する巡礼者を保護したのだが、保護の仕事には巡礼者の財産の保全も含まれていた。巡礼者がヨーロッパ内で財産を騎士団に預け、聖地で引き出せるようにしたのである。

時代が進むと騎士団は金融サービスを拡大し、戴冠用宝玉を担保に君主にカネを貸すまでになっていた。テンプル騎士団は1312年に解散したが、彼ら以外の金融業者は融資事業を拡大しつづけた。1500年代には商人がヨーロッパ中の見本市で負債を売り買いするようになった。

fire and brimstoneで「地獄の責め苦(業苦)」を象徴する表現。preachがつけば、聖職者が信者に向けて「地獄の責め苦について説教する、力説する」という意味になり、これも慣用表現。

Eventually kings, politicians, and business people embraced usury wholesale, and the Church looked the other way.

In 1462, Franciscan monks in Italy created the first non-profit pawnshops or monti di pieta (‘banks of piety’), which went on to spread across Europe. The idea was to be like a Grameen Bank in Renaissance Italy ― a lender of last resort, displacing loan sharks who extorted desperate borrowers. The Pope went on to approve ever more kinds of financial instruments, until lending with interest was effectively allowed.

その後、王も政治家も事業者も高利貸しを全面的に受け入れたのだが、(高利を是認できない)教会は別の方法を思いついた。

1462年、イタリアのフランチェスコ会修道士がモンティ・ディ・ピエタ(「敬虔なる銀行」)を設立。これは非営利目的だが、教会史上初の専門金融サービスであり、今日の質屋に近い存在である。モンティ・ディ・ピエタはその後ヨーロッパ全域に支店網を広げた。モンティ・ディ・ピエタは、高利貸しの取り立てに苦しむ借り手を救済する最後の砦となるべく設立されたイタリア・ルネッサンス版グラミン銀行のような機関だと思えばいい。この後、ローマ教皇はさらに多様な金融商品を公認していき、最終的には利息付き融資を事実上認めるに至る。

ここでは副詞として使われている。「大がかりに」「全面的に」の意味。

高利貸しが容認されていった理由

Despite the many loopholes and exceptions, usury laws still had teeth. ‘It would be a mistake to regard the Church’s sweeping prohibition as a sort of Volstead Act respected only by partisans, casually enforced, and lightly regarded,’ write the economic historians Sydney Homer and Richard Sylla in A History of Interest Rates (2005).

So why did the prohibition on usury fade away?

しかしどんなにたくさんの抜け穴や例外があろうとも、高利貸し禁止法は生きていた。経済学者のシドニー・ホーマーとリチャード・シラーは著書”A History of Interest Rates”(2005年)で「教会の徹底的な高利貸し禁制を、たまに適用され、軽く見なされるような禁酒法の一種、支持者のみが尊重する内輪の法と考えるのは間違いだろう」と指摘している。

ではなぜ、高利貸しの禁止はフェイドアウトしていったのだろうか?

理由1: 利子の禁止自体が一種のポーズだった

One interpretation is that it was simply dogma ― just like the belief that the Sun revolves around the Earth ― that diminished in force as the Catholic Church splintered and lost political authority.

Consider the Church like a business, whose core product was salvation, the economists Robert B Ekelund and Robert F Hebert have argued. When the Catholic Church held a monopoly in Europe, the clergy could ‘sell’ salvation at high prices ― including strict prohibitions and purchased ‘indulgences’, which usurious sinners could buy in order to be absolved.

But in the 1500s, during the Reformation, theologians such as Martin Luther denounced these practices. They advocated a more direct relationship with God that did not rely on priests as intermediaries, and founded new Christian movements such as Protestantism. The effect was that of a new company undercutting a monopoly.

As Christian factions competed for believers, it led to a faith-based ‘race to the bottom’. And to increase their appeal, sects made fewer demands on believers ― which meant weakening their stance on usury.

ひとつには、天動説と同じく建前の教義に過ぎなかったという解釈が存在する。ローマ教会が分裂し政治的権威を失うにつれ、教会の禁制が実効性を失っていったというのである。

経済学者のロバート・B・エケルンドとロバート・F・エバートは、教会を会社にたとえる。この会社の主力商品は「救済」である。ローマ教会が「救済」市場を独占していれば、聖職者は「救済」を高値で「売る」ことができる。厳格な禁止という前提の下、高利貸しは教会から「贖宥状」という「救済」を買うことで罪の赦しを得る仕組みができあがった。

しかし、16世紀になると宗教改革を先導したマルティン・ルターらの神学者は、このような慣行を猛烈に非難した。ルターらは司祭を仲立ちとするカトリックではなく、神と直接向き合う信仰を求め、プロテスタント主義に代表される新しいキリスト教運動を創始した。ビジネスにたとえれば、老舗の独占を突き崩す新興企業の誕生である。

キリスト教が複数の宗派に分裂し、信者獲得競争を始めると、宗教界の「底辺へのレース」が始まった。自分の宗派を少しでも魅力的に見せるために、信者への要求はどんどん緩くなる。そしていつの間にか、高利貸しに対するスタンスも軟化していったのである。

すべて宗教的概念。とくにsalvation(救済)とindulgence(贖宥状)は重要。前者は一神教が多神教を制した鍵となる概念。現世における罪の意識と来世における救済はセットとなる概念。

後者はローマ教会の成れの果て(堕落)を象徴する歴史的物証として重要。日本語ていう免罪符に近い。金銭を受け取る代わりに罪を許す。つまり高利貸しの禁止という看板(建前)を掲げつつ、「救済」の名の下に金儲け(本音)を行ったのだから明らかな欺瞞的行為である。

このように宗教的概念を理解していると英語の読解力だけでなく文化背景の理解も進む。その上ボキャブラリーの充実にも役立つ。

理由2: 経済発展が進み融資を制約する必然性がなくなった

Here’s another view on why usury became less sinful: economic development eventually meant it wasn’t worth the trade-off.

In 16th-century Europe, the economy was shifting from one defined by local agriculture to centres of commerce such as Florence. Global expansion made loans and investments more profitable, even as gold arriving from South America caused inflation. In these circumstances, the opportunity cost of not lending money grew higher and higher, as Scheinkman and Glaeser have argued.

高利貸しへの罪悪感が薄れていった理由については別の見方もある。先ほども名前を挙げたシャインクマンとグレーザーによれば、経済発展の結果、その成果とトレードオフで信仰を守るような人間がいなくなったというのである。

16世紀のヨーロッパでは、すでに経済の中心は地方の農業共同体から、フィレンツェのような商業都市へシフトしていた。経済は地球規模に拡大しており、たとえ南米から輸入したゴールドがインフレを引き起こしたとしても、融資と投資にはそれ以上の旨味があった。こうした状況では、カネを貸さないリスク、いわゆる機会損失の方が問題になる。

In addition, the spread of banking ultimately transformed credit from a personal transaction between neighbours to a competitive, impersonal market.

In The Idea of Usury (1949), the sociologist Benjamin Nelson argued that this institutional shift led Europeans to view moneylending more favourably during the Reformation. Luther interpreted Bible passages about usury, especially those that condemned charging interest on the poor, as calls to act generously. Usurers commit a sin, Luther wrote, only when their actions violate the do-unto-others principle ― that is, only if ‘they do not want to be treated this way in return by others’. This reciprocity meant merchants and wealthy families were allowed to charge each other interest. Luther asked Christians to offer the needy charity rather than loans ― but he still accepted interest rates under 5 per cent.

さらに銀行業の普及によって、信用取引は、隣人同士のカネの貸し借りの次元から、匿名性の高い競争市場での資金融資へ軸足を移した。

社会学者ベンジャミン・ネルソンは著書”The Idea of Usury”(1949年)で次のように論じる。宗教改革の時代、このような信用制度の進展を通じて、ヨーロッパ人は金貸し行為を好意的に捉えるになっていった。ルターの解釈によれば、聖書の高利貸しを諫める章句、とりわけ貧者への利貸しに対する非難は、神による寛容性の要求なのである。

ルターは、高利貸しが罪を犯すのは「己の欲する所を人に施せ」の原則に反する行動をとったときのみである、と書いている。「人が他人にそのように扱われることを望まない」ことをした場合だけが罪に問われるというのである。この互恵主義を採れば、商人と富裕層相互の貸し出しに利子を課すことは許されるべき行為となる。ルターは、貧しい人たちにはカネを貸すのではく施すようキリスト教徒に求めたが、それでも5%未満の金利は認めていたのである。

事実上の金利規制解除

Surely we’re well rid of this moralising approach to finance. A world without interest payments would be one in which few people could access the funds they need to attend college, buy a house, or start a business.

John Calvin, the French Reformation leader, thought it was immoral that his countrymen raised prices in order to take advantage of a flood of Protestant refugees who arrived in Geneva; but, just as surge pricing can recruit more Uber drivers on New Year’s Eve, we know that high prices also work to send a signal so that goods can flow to where they are needed.

But this isn’t the full story. The rise of debt wasn’t the Church simply bowing to the inevitable. Members of the clergy played an active role in creating the mindset that allowed usury to become respectable.

この段階まで来ると、金融に対する伝統的、道徳的タブーは解除されたといえるだろう。利払いのない世界では、大学に通うカネ、家を買うカネ、ビジネスを始めるカネを借りられる人がほとんどいなくなってしまうからだ。

フランス生まれの宗教改革者ジャン・カルヴァンは、ジュネーブに大量のプロテスタント難民が押し寄せたのをいいことに、便乗値上げにいそしむ同胞たちを不道徳だと非難した。しかし物価が上がると大晦日に雇えるUberの運転手が増えるように、高値は商品の需要があるというシグナルでもある。

もっとも話はこれで終わらない。借金が一般化したのは単に教会が必然的な成り行きに屈したからではなかったのだ。むしろ聖職者が積極的な役割を果たすことで、高利貸しが尊敬すべき職業だという通念が作り出されていったのである。

「someone (something)に屈する」、「someone (something)を認めざるをえない」といった不本意な対応を意味する。

ここで記事はいったん中断して、過去の偉人たちが金融や高利貸しについて何と言っているか見ておこう。これらを読む限り、現代人が相当なアノマリーな社会状況に生きていることが歴然とわかる。

金融と高利貸しにまつわる名言集

トマス・ジェファーソン(第3代アメリカ大統領)

“I believe that banking institutions are more dangerous to our liberties than standing armies. If the American people ever allow private banks to control the issue of their currency, first by inflation, then by deflation, the banks and corporations that will grow up around [the banks] will deprive the people of all property until their children wake-up homeless on the continent their fathers conquered. The issuing power should be taken from the banks and restored to the people, to whom it properly belongs. Paper is poverty… it is only the ghost of money, and not money itself.”

(Thomas Jefferson, Founding Father, 3rd US President, and Author of the “Bill Against Usury”)

意訳:アメリカの自由にとって銀行屋は軍隊より脅威。私有銀行が通貨を発行するようになったら、畢竟、国民はケツの毛まで抜かることになる。通貨発行権を本来あるべき国民の手に戻せ。札は貧困の象徴だ。あんな紙切れ、カネではない。カネの亡霊だ。

注意::ここでprivate banksといっているのは、現代スイスなどのプライベートバンクの意味ではなく、国有でない民間資本の銀行を指す。実際、現在のFRBは中央銀行ということばで煙に巻いているが、国有組織ではなく民間資本の銀行に過ぎない。金融緩和をすればするだけ株主には配当が支払われている。

ジョン・アダムス(第2代アメリカ大統領)

“Banks have done more injury to the religion, morality, tranquility, prosperity, and even wealth of the nation than they can have done or ever will do good.”

(John Adams, Founding Father and 2nd US President)

意訳:銀行は国の信仰、道徳、平安、豊かさ、そして富にとって百害あって一利なし。

アンドリュー・ジャクソン(第7代アメリカ大統領)

“You (the bank) are a den of thieves and vipers, and I intend to rout you out, and by the Eternal God, I will rout you out.”

(Andrew Jackson, 7th US President)

意訳:お前ら銀行屋は悪の巣窟。天壌無窮の神の名において、この国からお前らを叩き出してやる。

エイブラハム・リンカーン(第16代アメリカ大統領)

“I see in the near future a crisis approaching that unnerves me and causes me to tremble for the safety of my country; corporations have been enthroned, an era of corruption in High Places will follow, and the Money Power of the Country will endeavor to prolong its reign by working upon the prejudices of the People, until the wealth is aggregated in a few hands, and the Republic is destroyed.”

(Abraham Lincoln, 16th US President)

意訳:危機が迫っている。国の安寧を考えると体が震える。民間会社が玉座に坐れば、カネの力にあかせて国民をたばかり延命を図るだろう。そのうちにも富は少数の手に渡り、この共和国は崩壊してしまう。

ヘンリー・フォード(フォード社創業者)

“The one aim of these financiers is world control by creation of inextinguishable debts.”

(Henry Ford American Industrialist, Founder of the Ford Company)

意訳:金融家の主たる目的は返しきれない負債を作り出して世界を支配することにある。

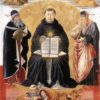

アリストテレス

“The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it. For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. . . Wherefore of all modes of getting wealth this is the most unnatural.”

(Aristotle, Greek philosopher and scientist)

意訳:「最大限の理性をもって最も憎べきもの、それは高利貸しである。なぜなら、高利貸しは貨幣の本来の目的たる交換からではなく、貨幣そのものから儲けを得る行為だからである。貨幣は売り買いに用いるべきもので、利子を使って殖やすために用いるべきものではない。高利貸しはあらゆる殖財手段のうち、最も自然に反した行いである。」『政治学』

アリストテレスは人間の交換行為のうち「金儲けを目的とした交換」をクレマティスティケ(理財術、殖財術。英語ではchrematistics)と呼んで蔑んだ。したがって利子も嫌った。この考えは中世のキリスト教にも大きな影響を与えたと思われる。

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません