【金融の歴史01】高利貸しのタブーが解かれたのはなぜか?金貸しへの抵抗感の消失

今回から数回にわたって金融の歴史について考えてみたいと思う。

金融史のターニングポイントは利子タブーの解放

利子は長く禁止されていた。その禁止が説かれた瞬間、パンドラの箱が開いた。

仮想通貨には利子がつかない。フィアットマネーではなくゴールドに「わざと」似せてあるのだ。その「わざと」の意図を知るには、「なぜ一般の通貨には禁じられていたはずの利子は許されるようになったのか」を知っておく必要がある。

利子の問題には宗教が絡んでいる。教会と銀行は切っても切れない関係にあり、さらにいうなら戦争と金貸しが結びつくことで歴史は大きく舵を切った。

この辺りに関する英文記事を英日対照形式で紹介しよう。

金貸しはいかにして罪であることをやめ、社会的信用のある仕事になったのか?

銀行家と神学者の取り合わせ

‘A banker and a theologian’ sounds like the start of a bad joke. But for David Miller it’s merely a job description. After working in finance and business for 16 years, Miller turned to theology, and received his PhD from Princeton Theological Seminary in 2003.

Now he’s a professor of business ethics and the director of Princeton University’s Faith and Work Initiative, where his research focuses on Christianity, Judaism and Islam. ‘How to Succeed without Selling Your Soul’ is the students’ popular nickname for his signature course.

銀行家にして神学者と聞けば悪い冗談と思われるかもしれない。だがデヴィッド・ミラーは実際に両方の職をもっている。金融やビジネスの世界で16年間働いた後、ミラーは神学者に転身した。

2003年にプリンストン神学校で博士号を取得した。現在、ビジネス倫理学教授として、プリンストン大学の研究所Faith and Work Initiativeで主にアブラハム宗教を研究している。「魂売らずに成功する方法」、これがミラーの講義に学生がつけたあだ名である。

シティバンクで哲学談話

In 2014, Citigroup called. The bank had been battered by successive scandals and a wave of public mistrust after the financial crisis, so they wanted to hire Miller as an on-call ethicist. He agreed. Rather than admonish bankers to follow the law – an approach that Miller thinks is inadequate – he talks to them about philosophy.

Surprisingly, he hasn’t found bankers and business leaders to be a tough crowd. Many confess a desire to do good. ‘Often I have lunch with an executive, and they say: “You do this God stuff?”’ Miller told me. ‘And then we spend next hour talking about ethics, purpose, meaning. So I know there’s interest.’

Miller wants people in finance to talk about ‘wisdom, whatever its source’. To ignore these traditions and thinkers, as the bulk of the industry tends to do, is equivalent to ‘putting on intellectual blinders’, he says.

2014年、金融危機に端を発する社会の不信と相次ぐ不祥事で弱り目に祟り目だったシティバックから電話があった。オンコールの倫理学者として来てくれないかという。ミラーは承諾したが、彼の思いついたアプローチは場違いに思えた。バンカーたちに法に従うよう諭す代わりに、哲学を教え始めたのだ。

驚いたことにバンカーたちは抵抗しなかった。多くの者は何かいいことをしたいのだと告白した。「よく幹部とランチを一緒に食べたのですが、『そんな神のようなことをしてるんですか』と彼らはいうんです」とミラーはわたしに言う、「それから小一時間、倫理や意義や意味について話しました。脈があるなと思いました」。

ミラーは金融のプロに、どんなネタ元でもいいから叡智について話すよう促した。多くの業界でやるように、業界のしきたりや経営哲学について話すのは「知性に目隠しをつける」ようなものだとミラーはいう。

金貸し観の変遷:中世まで

Today, a banker listening to a theologian seems like a curiosity, a category error. But for most of history, this kind of dialogue was the norm. Hundreds of years ago, when modern finance arose in Europe, moneylenders moderated their behaviour in response to debates among the clergy about how to apply the Bible’s teachings to an increasingly complex economy. Lending money has long been regarded as a moral matter. So just when and how did most bankers stop seeing their work in moral terms?

神学者に耳を傾ける銀行家は、いまでこそ好奇の対象、お門違いにしか思われないが、昔は当たり前だったのである。何百年も前、ヨーロッパに近代金融が勃興していた頃、聖職者の間では、複雑になる経済にどうすれば聖書の教えをうまく適用できるかが議論されていた。カネの貸し手は聖職者の意見に背かぬよう行動を律した。金貸しは長い間、道徳に反する行為とみなされていたのだ。では、いつから、なにがきっかけで銀行家は金貸しに罪悪感を感じなくなったのだろうか?

金貸しは悪魔と同列

In the early 1200s, the French cardinal Jacques de Vitry wrote a collection of exempla, morality tales that priests used in their sermons. In one story, a dying moneylender makes his wife and children swear to hang a third of their inheritance around his neck, and to bury him with it. His family does as instructed. However, later they decide to open the man’s grave to recover the money – only to flee ‘in terror at seeing demons filling the dead man’s mouth with red hot coins’, de Vitry wrote.

1200年代のはじめ、フランスの説教師ジャック・ド・ヴィトリは説教で使う訓話や道徳譚を多くものしたが、そのひとつに、息も絶え絶えの金貸しが、相続財産の3分の1を自分の首にかけ、自分死体と一緒に埋めることを女房と子どもに誓わせたという話がある。遺族は言いつけ通りにした。しかし後で気が変わって墓を暴くと、悪魔が死者の口を真っ赤に燃えるコインで埋め尽くしているところだった。彼らは恐ろしくて一目散に逃げ出した、という。

In de Vitry’s world, the moneylender deserved to be defiled by demons, because he’d committed the sin of usury – charging interest on a loan. De Vitry didn’t care whether the rate was high or low, because the Church’s position was that extracting a single cent of interest was evil. The roots of this revulsion run deep, and across cultures. Vedic law in Ancient India condemned usury, and rulers routinely capped interest rates from Ancient Mesopotamia to Ancient Greece. In Politics, Aristotle described usury as ‘the birth of money from money’, and claimed it was unnatural because money was sterile and should not ‘breed’.

ド・ヴィトリの時代、金貸しと悪魔といわれても仕方ないと思われていた。金貸しは貸した金に利子をつけて貸す、高利貸しという罪を犯す者だったからだ。ド・ヴィトリは高利、低利を問わない。教会にとってわずかでも利子を取ること自体が悪だったのだ。この利子に対する憎悪は根が深い。各地の文化に共通している。古代インドのヴェーダの法は高利貸しを禁じていた。古代メソポタミアからギリシャに至るまで支配者は金利を恒常的に制限していた。政治学の分野でもアリストテレスは高利貸しを「カネがカネを生む」と形容し、貨幣は不毛であり、何物も生むべきでないから不自然な行為だと断じている。

ユダヤ・キリスト教の利子禁止の伝統

Judeo-Christian religions cemented the usury taboo. The Old Testament reads: ‘Do not charge a fellow Israelite interest,’ and the Book of Luke advises: ‘[L]ove ye your enemies: do good, and lend, hoping for nothing thereby.’

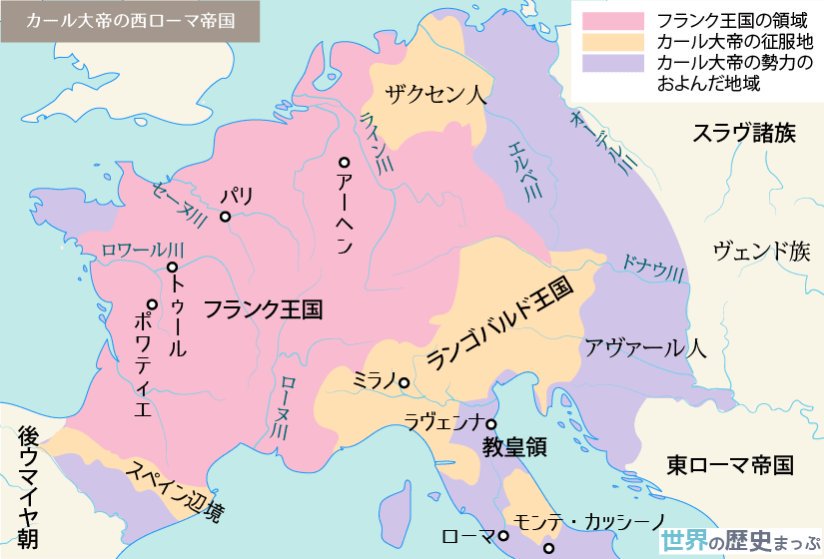

In the 4th century CE, Christian councils denounced the practice, and by 800, the emperor Charlemagne made the prohibition into law. Accounts of merchants and bankers in the Middle Ages frequently include expressions of anguish over their profits.

In his Divine Comedy of the 14th century, the Italian poet Dante Alighieri put the usurers in the seventh circle of Hell; in the case of Reginaldo Scrovegni, one Paduan banker singled out by Dante, his son ended up commissioning a chapel painted with frescoes by Giotto to expiate the family’s sin. Over the ensuing centuries, the philanthropy and patronage of other Italian Renaissance families such as the Medicis was partly inspired by guilt about how they’d profited from charging interest.

ユダヤ・キリスト教は高利貸しのタブー化を徹底した。旧約聖書には「兄弟に利息を取って貸してはならない」(申命記23.19)とあり、ルカ福音書には「あなたがたは、敵を愛し、人によくしてやり、また何も当てにしないで貸してやれ」(6.35)とある。

4世紀に入ってもカソリック評議会は高利貸しを非難し、800年頃にはカール大帝が法律で高利貸しを禁じた。中世の商人や金融業者の書いたものを読むと、しばしば彼らは儲けに対する苦悩を記している。

14世紀、ダンテ『神曲』のなかで高利貸しは地獄の第七圏第一の環に数えられている。金貸しの代表としてダンテが取り上げたパドヴァのレギナルド・スクロヴェーニには息子がいた。 その息子は贖罪のために教会を寄進し、壁面にジョットーの描いたフレスコ画を飾らせた。その後も、メディチ家はじめイタリア・ルネサンス期の貴族は盛んにフィランソロピーやパトロンを申し出ているが、ひとつには利子収入への罪悪が働いていたのではないか。

中世初期までは相互扶助の経済が主流だった

The stigma against moneylending continued well into the 1500s. To understand it, think about your reaction to the idea of a bank making a loan to a business at a 5 per cent interest rate. No problem, right? Now compare that to how you’d feel if your mother lent you money on the same terms.

In Biblical times, the typical loan was more like the second case – it wasn’t an arms-length transaction, but a charitable loan from a wealthy man to a neighbour who’d experienced misfortune or had nowhere else to turn.

Throughout early Medieval Europe, the local church or a wealthy family was often the only source of capital, especially outside the major commercial centres. Many peasants bought their land by getting mortgages from a monastery. In a world without credit markets and insurance, then, charging interest felt like extorting a friend or family member.

金貸しへの抵抗感は明らかに1500年代までは続いていた。この抵抗感を理解するには、銀行が5%の金利で会社に融資するといったとき、どう思うか想像してほしい。問題に思わないはずだ。では、あなたのお母さんが同じ条件でおカネを貸すといった場合はどう感じるだろうか。

聖書が書かれた時代、融資は後者のケースに似ていたのである。それは実勢価格での、いわゆるアームズレングス取引ではなく、裕福な人が不幸な隣人や寄る辺ない人に慈善的に貸し出すおカネだった。

中世初期までのヨーロッパでは、商業地を除けば、資本の出所といえば地元の教会か裕福な家庭くらいしかなかった。農民の多くが修道院から抵当権付きでおカネを借り、土地を買った。信用市場や保険がない世界で金利を取ることは、友人や家族をゆるすように感じられたのだ。

古代社会では相互信頼が債務と信用を規定していた?

In Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011), the anthropologist David Graeber argues that before the advent of money, economic life within a community was a web of mutual debts. People did not behave as self-interested individuals – at least not from the perspective of a single transaction; rather, they would share food, clothes and luxuries, and trust that their peers would repay the favour in return.

When we consider these origins of debt and credit – as a system of mutual aid between people who trust each other – it’s no surprise that so many cultures viewed charging interest as morally wrong.

人類学者デヴィッド・グレーバーは著書『負債論 貨幣と暴力の5000年』の中で、貨幣の生まれる前、コミュニティ内の経済生活はお互いの貸し借りで成り立っていたのではないかといっている。人間は自己利益では動かなかった。少なくても個別の取引の観点で行動を決めることはなかった。むしろ彼らは食べ物、衣服、贅沢品を分かち合い、お互いに借りれば返すという暗黙の信頼のうちに生きていた。

これらを債務と信用の起源と見なすなら、つまり、お互いを信頼する人々の間の相互扶助のシステムだと見なすなら、多くの文化が利子を課すことが道徳にもとると考えられたとしても何ら不思議はないだろう。

Moreover, as the economists José Scheinkman and Edward Glaeser have noted, usury laws also acted as a kind of social insurance that reduced inequality. Since charging interest (especially extortionate interest) was condemned, poor people could get emergency loans quite cheaply, and the rich couldn’t easily and passively turn their wealth into more wealth.

At least that was the idea – in reality, people often turned to loan sharks, or to wealthy Jews who were quite literally demonised for moneylending.

さらに、経済学者のホセ・シャインクマンとエドワード・グレーザーが指摘しているように、高利貸し禁止法は不平等を減らすための、一種の社会保証制度として機能していた可能性がある。金利賦課(とくに高利賦課)が禁止されていたために、貧しい人々は緊急のおカネを安く借りられ、富裕層が簡単に何もせず富から富を殖やすことは難しかったのである。

少なくともそれが理想だった。ただ現実には、多くの人が高利貸しや、文学作品上、悪徳金貸しのイメージがついている裕福なユダヤ人にすがったのである。

君主も教皇も必要に迫られ、戦費を負債で調達するようになった

Debt became essential to fighting wars, which both monarchs and the Pope needed to fund

Some historians and economists contend that the usury taboo was more about performance than reality. They argue that the moneyed class mostly ignored the prohibition ― not least because it called for unrealistic levels of charity from the gentry.

Merchants and bankers had all sorts of tactics for disguising the interest payments; one trick was for the parties to agree to use an overpriced exchange rate for the purchase of goods in the future. Or lenders made loans that didn’t pay interest, exactly, but instead promised a share of the profits from the borrower’s business. (This was a loophole, but it also ensured bankers got paid only if their loans benefitted the borrowers.)

高利貸しのタブーは、現実に即した方策というよりパフォーマンスに近いものだったと一部の歴史家や経済学者は主張する。とりわけ、貴族や地主に法外ともいえる慈善的な貸し出しが要求される状況にあって、富裕層はほとんど禁止を無視していたのだ、と。

商人や金貸しはありとあらゆる偽装を施して、事実上の利払いを要求した。たとえば、法外な高値で将来の物品の購入を約束するとか、利息はびた一文取らない代わりに、貸出先のビジネスの上がりの何割かを受け取る契約をするなどである(後者は法の抜け穴だが、金貸しは融資が借り手が利益を出した場合のみ、分け前をもらう約束になっていた)。

「とりわけ~のため」、「~だからなおさら」。~以下の強調表現。

煉獄の発明

Meanwhile, the Catholic Church played its own part in sowing the seeds of a change of attitude. In the 13th century, it developed the concept of Purgatory ― a place that had little basis in scripture but did offer some reassurance to anyone committing the sin of usury each day.

‘Purgatory was just one of the complicitous winks that Christianity sent the usurer’s way,’ wrote the historian Jacques Le Goff in Your Money or Your Life: Economy and Religion in the Middle Ages (1990). ‘The hope of escaping Hell, thanks to Purgatory, permitted the usurer to propel the economy and society of the 13th century ahead towards capitalism.’

一方、カトリック教会は教会で、利子への態度を少しずつ変化させていった。 13世紀には煉獄(Purgatory)という概念を考案した。煉獄は聖書に書かれているわけではなく、日々高利貸しの罪を犯す者に安心立命を与える手段であった。

歴史家のジャック・ル・ゴフはその著書”Your Money or Your Life: Economy and Religion in the Middle Ages”(1990)の中で、 「煉獄は、キリスト教が高利貸しに送った共謀サインのひとつに過ぎない。地獄を逃れて煉獄に留まるという希望が、高利貸しに13世紀の経済と社会を活性化する口実を与え、後の資本主義を準備した」と指摘している。

この世と天国の間にあるとされる贖いの場所、または期間。ダンテの『神曲』は地獄(Inferno)めぐりを経て煉獄(Purgatorio)に至り、最終的に天国(Paradiso)へ至る遍歴もの。煉獄編ではカトリックの「七つの大罪」(seven deadly sins)概念に合わせて7つの冠と呼ばれる世界が描かれる。

本音と建前のはざまに揺れ動く人間の社会はいまも昔も変わらない。金銭にまつわる「態度」の変化も例外ではない。当時は教会の権威が絶大であり、煉獄の「発明」などを通じて徐々に現実への適応、すなわち世俗化→近代化への道が用意されていく。

この続きは次回に譲る。

金貸しにまつわる英語

一般に金貸し業はmoney lending、金貸し業者はmoney lenderという。サラ金、違法金貸し業者などはloan shark。関連で質屋はpawnbroker、pawn shop。

ロンバード一族

金融業、とくに質屋業で隆盛を誇ったのがロンゴバルド人(英語ではLombard、ロンバード)だ。

質屋は利子を禁じる中世社会で抜け道として発達した商売。担保をとり、返済不能に陥れば高値で買い取る契約で、事実上、上乗せ分が利子であった。この商売は大いに流行ったが、これを一手に牛耳ったのがロンゴバルド人だった。彼らは6世紀後半にイタリア北部に攻め込み、半島の多くを配下に収めた。出身はスカンディナビア半島、エルベ川周辺に定着した後、南下したゲルマン系民族(ロンゴバルド王国)。現在でもヨーロッパの多くの都市にロンバード通りが存在するのは彼らの質屋があった名残り。

一般名詞でlombardといえば、まず第一にミラノのあるロンバルディア州(Lombardia)の人を意味するが、文脈によっては「銀行家」、「金貸し」の意味になる。

同様に、シェークスピア『ヴェニスの商人』の悪役金融業者シャイロックはあまりにも有名なので、shylockは動詞としても(高利貸しする)、一般名詞としても(高利貸し)使える。

usury、usurer

歴史的な文脈ではよくusury、usurerが使われる。語源は以下の通り。

c. 1300, “practice of lending money at interest,” later, at excessive rates of interest, from Medieval Latin usuria, alteration of Latin usura “payment for the use of money, interest,” literally “a usage, use, enjoyment,” from usus, from stem of uti (see use (v.)). From mid-15c. as “premium paid for the use of money, interest,” especially “exorbitant interest.”

ラテン語の “usuria”(”usage”、”use”の意味)から来ており、当初はネガティブな意味を持っていなかった。単なる「ご用立て」である。高利貸しという職業が一般化し、悪徳業者も出てきて悪いイメージが定着するのは15世紀以降のようだ。ちなみに「暴利をむさぼる」というときの暴利は、”exorbitant interest” という。

金貸しの簡単な歴史については以下のwikipedia記事が参考になる。

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません