【ドラッカーの思想】”時代遅れ” とされたキルケゴールの遅れようがない実存哲学(後編)

前回紹介したのは、ドラッカーがキルケゴールに学んだ人間の実存の定義だった。人間は社会的存在であると同時に霊的存在である。理性主義者は社会改良に力を傾けすぎて自滅し、猛烈な反理性主義の反動を引き起こしてホロコーストやスターリンの粛清を招いた。今回はその続きである。

19世紀的進歩主義と実存

It was the very essence of all nineteenth-century creeds that eternity can and will be reached in time; that truth can be established in society and through majority decision; that permanence can be obtained through change. This is the belief in inevitable progress, representative of the Nineteenth Century and its very own contribution to human thought.

時間のなかで永遠に到達できる―、これこそ19世紀の究極的な信念である。それは社会のなかで多数者の決定を通じて真理を確立できると信じ、変化を通じて永遠を獲得できると信じるのである。進歩の不可避性を信じること―、これこそが19世紀を代表する人類思想史への貢献である。

定性的価値の量への転換

You may take the creed of progress in its most naive and therefore most engaging form – the confidence that man automatically and through his very sojourn in time becomes better, more nearly perfect, more closely approached the divine. You may take the creed in its more sophisticated form – the dialectic schemes of Hegel and Marx in which truth unfolds itself in the synthesis between thesis and antithesis, each synthesis becoming in turn the thesis of a new dialectical integration on a higher and more nearly perfect level.

Or you may take the creed in the pseudoscientific garb of the theory of evolution through natural selection.

In each form it has the same substance: a fervent belief that by piling up time we shall attain eternity; by piling up matter we shall become spirit; by piling up change we shall become permanent; by piling up trial and error we shall find truth. For Kierkegaard, the problem of the final value was one of uncompromising conflict between contradictory qualities. For the Nineteenth Century, the problem was one of quantity.

最も素朴な、それゆえ最も熱狂的な進歩信仰は、人間が時間相に滞留する間に自動的に改善し、完全となり、神聖なものに接近していくと考える。もっと洗練された形式になると、たとえばヘーゲルやマルクスの弁証法的正反合一の思想においては、あるテーゼとアンチテーゼの統合でもたらされたジンテーゼは、別のより高次で完全なレベルの弁証法的統合の基礎となる。

これと同様の進歩への信仰は、疑似科学的な外装をとってダーウィンの自然淘汰的進化論を反映する。形式は違えど実質はひとつ、熱病のような進歩の確信である。

時間を積み上げれば永遠に辿り着く、物質を積み上げれば霊性に至る、変化を積み重ねれば永遠に持続する。こう言い直せる。キルケゴールにとって、妥協しえない質と質の衝突こそが最終的価値であった。19世紀にとってそれは量の問題に還元しうる問題だったのである。

楽観主義

Where Kierkegaard conceives the human situation as essentially tragic, the Nineteenth Century overflowed with optimism. Not since the year 1000, when all Europe expected the Second Coming, has there been a generation which saw itself so close to the fulfilment of time as did the men of the Nineteenth Century.

キルケゴールが人間の実存が置かれた状況を本質的悲劇と認識していた一方で、19世紀は楽観主義に満たされていた。キリスト再臨が意識された西暦1000年以降で、19世紀の人間ほど時間の完成に意識を傾けた世代は存在しない。

悲劇と破滅の捨象

In this creed of imminent perfection, in which every progress in time meant progress toward eternity, permanence, and truth, there was no room for tragedy (the conflict of two absolute forces, of two absolute laws). There was not even room for catastrophe. Everywhere in the nineteenth-century tradition the tragic is exorcised, catastrophe supressed.

A good example is the attempt – quite popular these last few years – to explain so cataclysmic a phenomenon as Hitlerism in terms of “faulty psychological adjustment,” that is, as something that has nothing to do with the spirit but is exclusively a matter of techniques.

Or, in a totally different sphere, compare Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra with Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and see how the essentially tragic “eros” becomes pure “sex” – psychology, physiology, even passion, but no longer a tragic, i.e., an insoluble, conflict.

Or one might, as one of the triumphs of the attempt to suppress catastrophe, take the early Communist explanation of Nazism as “just a necessary stage in the inevitable victory of the proletariat.” There you have in purest form the official creed that whatever happens in time must be good, however evil it is. Neither catastrophe nor tragedy can exist.(中略)

(進歩思想の)完成が差し迫っているという信念にあっては、時間相における個々の進歩が永遠と真理への前進を意味するから、そこに悲劇―絶対的な力の相克、絶対的な法の相克―が自覚される余地はない。破滅さえ認識される余地はない。19世紀の伝統はあらゆる細部において悲劇を追い払い、破滅を抑圧した。

その好例がここ数年とても流行っている、ヒットラー主義の大惨事を「誤った心理学的調整」と見なす傾向である。この惨事は霊性とは無関係で、ひとえに政治技術的な失敗だったというのだ。

まったく別の分野に目を転じれば、シェークスピアの『アントニーとクレオパトラ』とフローベールの『ボヴァリー夫人』が鋭い対照をなす。解消不能な対立であるがゆえに前者の「エロス」は本質的な悲劇だが、後者ではそれが純粋に「セックス」の―病理学や心理学や情熱の―問題に置き換わっている。

またコミュニストのナチズムに関する説明―「プロレタリアートの不可避の勝利に向け単に必要な段階」―には、破滅を抑圧せんとする欲求の勝利がよく表れている。これは最も純粋な意味で、それがどんな悪魔的な事態であろうと、時間相に生じる事態はすべて善なのだという信仰の公的言明と呼べるものだ。そこに破滅や悲劇の出番はないのである。(中略)

残る死の問題

Yet however successful the Nineteenth Century was in suppressing the tragic, there is one fact that could not be suppressed, one fact that remains outside of time: death.

It is the one fact that cannot be made general but remains unique, the one fact that cannot be socialized but remains personal. The Nineteenth Century made every effort to strip death of its individual, unique, and qualitative aspect. It made death an incident in vital statistics, measurable quantitatively, predictable according to the actuarial laws of probability. It tried to get around death by organizing away its consequences. Life insurance is perhaps the most significant institution of nineteenth-century metaphysics; its proposition “to spread the risks” shows most clearly the nature of the attempt to consider death an incident in human life rather than its termination.

And the Nineteenth Century invented spiritualism – an attempt to control life after death by mechanical means.(中略)

だが、どんなに19世紀が悲劇を抑圧しおうせたかに見えても、抑圧しえないひとつの事実、時間相の外部に残る事実がある。死だ。

死は一般化しえず固有なものに留まる事実、社会化しえず個人的たらざるをえない事実である。19世紀は、死を定性的に扱わずに済むよう、死の個人性や固有性を取り去ろうとあらゆる努力を傾けた。死を保険の確率論に従う、予測かつ計測可能な人口動態統計の事象にしようとした。死をバラバラの帰結に切り分け、死全体を考えないようにした。生命保険は、おそらく19世紀の形而上学を最も特徴づける制度だといえるだろう。リスクの分散なる概念は、死を人生の結末ではなく一種の事故とみなす試みの本質を、最も明確に表している。

そして19世紀はスピリチュアリズムを発明し、機械的な手段で死後の生を制御しようとしたのである。(中略)

絶望の襲来

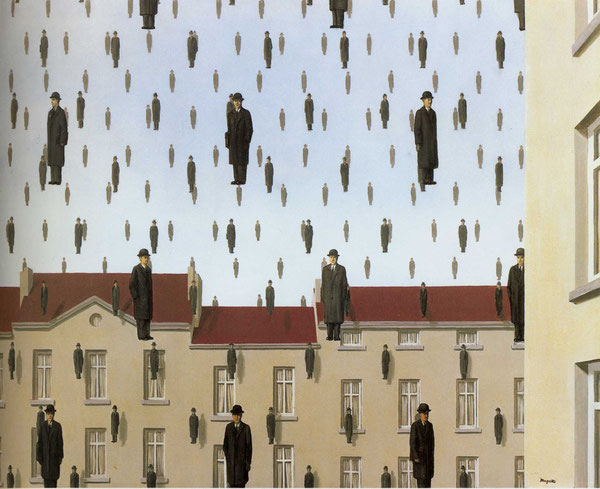

So long as death persists, the optimistic concept of life, the belief that eternity can be reached through time, and that the individual can fulfill himself in society, must have only one outcome – despair.

Suddenly every man finds himself facing death; and at this point he is all alone; all individual. If his existence is purely in society, he is lost – for now this existence becomes meaningless. Kierkegaard diagnosed the phenomenon and called it the “despair at not willing to be an individual.”

Superficially, the individual can recover from this encounter with the problem of existence in eternity; he may even forget it for a while. But he can never regain his confidence in his existence in society. Basically he remains in despair.

時間のなかで永遠に到達できるという信仰、社会のなかで個人が完全に自己を実現できるという信仰。このような楽観的な人生観は、死がある限り、ひとつの帰結に至らざるをえない。絶望である。

そのとき人は突如、死との対峙を迫られる。死に向き合うとき人はまったくひとりで、素の個人である。もし実存の根拠が社会というなら、死に直面した実存は逃げ場を失い、無意味化する。キルケゴールはこの現象をよく観察し、「個人であろうとしない絶望」と名づけた。

この永遠相における実存の問題に遭遇した個人は、うわべだけなら実存を取り戻せるし、当座の間、問題を忘れることもできようが、それでも、社会的実存への確信は二度と回復しない。基本的には絶望のうちに留まるのである。

人生の無意味化

Society must make it possible for man to die without despair if it wants him to be able to live exclusively in society. And it can do so in only one way – by making individual life meaningless.

If you are nothing but a leaf on the tree of the race, a cell in the body of society, then your death is not really death; you had better call it a process of collective regeneration. But then, of course, your life is not real life either; it is just a functional process within the life of the whole, devoid of any meaning except in terms of the whole.

もし社会が社会的存在としてのみ生きることを人間に望むなら、人が絶望せず死ねるようしなければならない。そのたけの唯一の方法は、個人の生を無意味化することである。

ひとりの人間が種という樹木の葉っぱに過ぎず、社会という身体を構成する細胞に過ぎないならば、個人の死は根本のところで死ではなく、集合的再生の一プロセスといったほうが適切だろう。だがもしそうなら、個人の人生が本物の人生たりえないことは自明だ。個人の人生は単なる機能的なプロセスであり、生の全体との関係においてのみ意味を持つ、ということになる。

Thus as Kierkegaard foresaw a hundred years ago, an optimism that proclaims human existence as existence in society leads straight to despair. And this despair can lead only to totalitarianism. For totalitarianism – and that is the trait that distinguishes it so sharply from the tyrannies of the past – is based on the affirmation of the meaninglessness of life and of the non-existence of the person.

Hence the emphasis in the totalitarian creed is not on how to live, but on how to die; to make death bearable, individual life had to be made worthless and meaningless. The optimistic creed, that started out as making life in this world mean everything, led straight to the Nazi glorification of self-immolation as the only act in which man can meaningfully exist. Despair becomes the essence of life itself.(中略)

こうして人間が社会的存在であると主張する楽観主義は、キルケゴールが100年前に予見したように絶望に直結する。絶望の行き着く先は全体主義以外考えられない。なぜなら、全体主義は人生の無意味さと人格の不在の確認に基づくものであり、この点で過去のどんな専制とも鋭く対立するからだ。

全体主義の教義はいかに生きるかよりいかに死ぬかを強調する。死を耐えられるものにするには、個人の生命に価値も意味もあってはならないからだ。ナチ思想において人生を唯一意味あるものに変える行為は自己犠牲である。現世の生をすべてと見なすことに始まった楽観主義は、そのまま自己犠牲の賛美に帰結し、絶望が人生そのものの本質となる。(中略)

信仰としての実存

ドラッカーによれば、カントやヘーゲルはこの絶望からの出口を理性に基づく人倫(徳、virtue)に求めた。しかし人倫は相対主義の罠を逃れえない。人倫が神なき世界の人間の内面に根拠を求める以上、万人に当てはまる普遍的な人倫など確立しようがないではないか。

もし普遍的な人倫を求めれば、人間は自由を失い、最終的に自己犠牲を払うか、絶望するしかない。キルケゴールは、人倫はより良い生活には役立っても、臨終の場面には無力であることをよくわかっていたのだ。こうして人間がふたたび袋小路に追い込まれる。では、キルケゴールはどうしたのか?

原文に戻ろう。

東洋的諦念か?それとも・・・?

Is then the only conclusion that human existence can be only existence in tragedy and despair? Are the sages of the East right who see the only answer in the destruction of self, in the submersion of man into the Nirvana, the nothingness?

Kierkegaard has another answer: human existence is possible as existence not in despair, as existence not in tragedy; it is possible as existence in faith. The opposite of Sin (to use the traditional term for existence purely in society) is not Virtue; it is Faith.

人間の実存は悲劇と絶望の実存でしかありえない―、それが唯一の結論になるのか?自我を滅却し、涅槃という無の境涯へ没入するのが唯一の答えと見た東洋の聖人たちが正しいのか?

キルケゴールは別の答えを用意した。彼によれば、人間の実存は絶望の実存でも悲劇の実存でもないものとして、信仰における実存として可能である。罪業(社会においてのみ実存することは伝統的に罪と呼ばれた)の反対は徳ではない。それは信仰である。

Faith is the belief that in God the impossible is possible, that in Him time and eternity are one, that both life and death are meaningful. Faith is the knowledge that man is creature – not autonomous, not the master, not the end, not the centre – and yet responsible and free.

It is the acceptance of man’s essential loneliness, to be overcome by the certainty that God is always with man, even “unto the hour of our death.”(中略)

信仰とは、神において不可能が可能になり、時間と永遠が一体化し、生と死が意味をもつという確信である。同時に、人間は自律的な存在でも主人でもなく、目的でも中心でもないことを自覚し、それでも人間は責任と自由を持つ創造物であることを認識することに他ならない。

信仰は人間の本源的孤独の受け入れである。人間の孤独は、神が「死の瞬間まで」人間ととともにあることの確からしさによって克服されるのである。(中略)

キルケゴールの到達点

Though Kierkegaard’s faith cannot overcome the awful loneliness, the isolation and dissonance of human existence, it can make it bearable by making it meaningful.

The philosophy of the totalitarian creeds enables man to die. It is dangerous to underestimate the strength of such a philosophy; for, in a time of sorrow and suffering, of catastrophe and horror, it is a great thing to be able to die. Yet it is not enough.

Kierkegaard’s faith, too, enables man to die; but it also enables him to live.

キルケゴールの信仰は、実存の恐るべき孤独、孤立と不調和を克服できない。しかし実存に意味を与えることで、人が耐えられるものに変える。

全体主義者の哲学は人が死ねる状況を作り出す。このような哲学の力を過小評価するのは危険だ。なぜなら悲しみと苦しみの時代、破滅と恐怖の時代にあって、死ねるということは素晴らしいことだからだ。にもかかわらず、そこには何かが足らない。

キルケゴールの信仰もまた死が可能な状況を生む。同時にそれは生が可能な状況を生むのである。

<記事引用終わり>

全体主義はいまもリアルタイムの問題

以上の論文の底に流れているのはアンチ理性主義・アンチ全体主義の実存思想である。実際、ヨーロッパ近代の歴史はすべて社会と霊性の折り合いをめぐる相剋だった。カトリックという組織宗教への反発がプロテスタントという新たな組織宗教を生み、キリスト教全体への反発が啓蒙思想を生み、その申し子である合理主義(理性崇拝)への反発が全体主義を生んで大量殺戮に帰結した。ナチズムもマルクシズムも霊性の問題の解決にはならなかった。

これでは、いったい何のための「神離れ」だったかわからない。欧米人の精神は深刻な危機に陥ったまま、いまも突破口を見出せない。

現代の全体主義

ドラッカーのマネジメント論は全体主義へのワクチンとして構想されている。企業は霊的存在としての人間に、社会以外の安心立命を与えるための場としてイメージされていたのである。私生活のドラッカーは保守的クリスチャンを任じ、神の御意(みこころ)の永遠の真理に奉じていた。

しかしマルクシストら全体主義者はソ連と関係なく「革命」を進めていた。彼らは下部構造(経済)から上部構造(文化)にターゲットを変え、マスメディアや大学を乗っ取って「社会改良」を始めた。

- 経済分野では、ハイエクらの自由主義を偽装しつつ、人間を「理性」的存在から「欲望人」に貶め、新自由主義を蔓延させた。イギリスのサッチャーが発病すると進行は早かった。アメリカのレーガンに伝染し、日本の中曽根政権に飛び火した。緊縮財政、民営化、規制緩和の三種の神器で公的部門の富を奪い「内国窮乏策」で先進国庶民の弱体化を進めた。ようやくトランプやBrexitでナショナリストの反撃が始まったものの、メディアはスクラムを組んで民の声を抑圧しようとしている。

- 社会分野でも「革命」は遂行中である。皮肉なことに、それは「実存主義者」サルトルのパートナーであるボーヴォワールのフェミニズムに端を発した。万国の労働者の代りに女性が「革命」主体に選ばれ、まず家庭という旧秩序が破壊された。さらに次なるターゲットとして性的弱者が選ばれ、ジェンダー理論による武装が始まると、社会正義を戦場する公序良俗の破壊が始まった。それはポリコレやセクハラやパワハラの装いのもと、日々メディアを賑わせている。

現在世界に蔓延しているネオリベラリズムとグローバリズムは新種の全体主義である。社会存在としての人間の範疇が「国家」から「国際社会」に移り、霊的存在としての人間が「理性」人から「欲望」人に変わっただけで、この全体主義が生みだすのは空っぽの自由、実存を持たない個人に過ぎないのではないか。

いまさら「神離れ」をキャンセルできないのはわかる。だが、所得や女性の社会進出やジェンダーフリーといった社会的生存条件の「改善」が、人間の実存の問題を解決するか?質の悪い冗談にしか見えない。キルケゴールがいったように、人間から死の問題は取り除けないし、霊的実存の問題は最後の最後まで残る。そのような意味で、キルケゴールが現代人に突きつけた実存の問題は「時代遅れになりようがない」のである。

◆アマゾン

イノベーターの条件―社会の絆をいかに創造するか (はじめて読むドラッカー (社会編))

◆楽天市場

イノベーターの条件 社会の絆をいかに創造するか/P.F.ドラッカー/上田惇生【3000円以上送料無料】

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません